Now_

Every second

Here_

Leuven

Min Choi and Sulki Choi

Whenever we try to take the slogan ‘age-old Leuven,

alive and kicking’ as a meaningful argument, we come to encounter

difficulty. There’s no problem in the ‘age-old’ part: it’s

a fact, as solid as the magnificent town hall. It’s the ‘alive

and kicking’ part that makes us wonder. Does it mean anything particular?

Can you think of any city that is not alive and kicking, but dead and

inert? Obviously we can’t. Both of us have spent some years of time

in a small American town called New Haven, widely regarded as one of the

most boring and unattractive cities in the US. But what we found there

was much life, and the same holds true to any other cities we have experienced.

At least for us, every city is alive and kicking: in a sense, that is

the very nature of the city.

On this reflection, we find ourselves striving for a more convincing case

of the ‘alive and kicking’ aspect of Leuven, leaving its historical

heritages and age-old charms aside. And here we’re supposed to be

talking about the ‘cultural life’ of the city. It has been argued

that ‘culture’ is not merely about the beautiful or the precious,

but also to be found in the way we work and play, the way we wear, eat

and drink: in short, the way we live our daily lives. Then we can expand

the arena of cultural life from museums and galleries to the ‘streets

level’ locales: libraries and newsstands; video rental shops and

record shops; clubs and bars; living rooms and wardrobes; even the dwellers’

handbags and pockets. Can we grasp and communicate the cultural life of

this microscopic scale? Can we reflect and express these local and banal

activities in such a way to form a collective ‘cultural identity’

of a city as a whole? These are the initial questions we’re having

in mind in approaching the problem of ‘cultural communication of

Leuven’. Following are some methodological notes we prepared to answer

the questions, at least partially, in the near future.

Emergence

The city is often compared to the living organism. Indeed, recent scientific

developments have provided us a better understanding of what seems to

be consistent in diverse ‘complex’ systems from the ants’

colony, human brain, computer software to the city. It is a self-organising

process, by which simple local events conjure up a higher-level order

without relying on any central plot or global perspective.[1]This

process, ‘the rise of a system that cannot be predicted or explained

from antecedent conditions’, is called ‘emergence’.[2]

And many have noticed this emergent process working in the city, with

its suburban clusters, for example, organising themselves in time without

any dictating plan.

Perhaps the basic principle of emergence, or self-organisation, is best

illustrated by the well-known Game of Life, designed by John Conway

in 1970.[3] This game

is ruled by a straightforward algorithm that regulates each cell’s

behaviour: first, a cell with one or no neighbour dies (for loneliness);

second, a cell with four neighbours also dies because of overpopulation;

third, with three neighbours it survives; fourth, an ‘empty’

cell with three neighbours becomes populated. When you run the program,

you will see some unpredictable patterns emerging, out of each cell’s

uncoordinated behaviours. Sometimes, the resulting pattern shows a well-developed

order which may seem as if planned in advance.

Some philosophers have attempted to explain the whole universe and the

mystery of life in terms of this self-organising process.[4]

But their theory might be less important here, than its practical implications.

In the world of politics, some activists of the so-called – and wrongly

labelled – anti-globalisation movement have been advocating the idea

of decentralised consensus decision-making, in place of the rule of majority.[5]

There is no central organisation or party apparatus to this movement,

but it didn’t deter the thousands of protesters gathered in Seattle

(1999), Genova (2001), and New York (2002), without any central command.

In the field of computer engineering, the ‘open source movement’

is based on the premise that spontaneous collaboration between willing

individuals is more productive than closed and protected authorship.[6]

There are some basic rules to this movement: you can freely access to

the source of a software, and modify or improve on it for your own purpose;

then the result should be returned to the public, to be shared and modified

again. Subsequently, the whole community will be benefited, with the software

getting increasingly smarter, as it absorbs feedbacks and local intelligence.

The free Internet encyclopedia Wikipedia

is a good example of this ‘peer-to-peer production’. It is free

to view, of course, but you can also freely contribute your own article,

or even edit the existing articles. Started in January 2001, Wikipedia

has grown to contain, at the time of writing, 182,465 articles in the

English version only.

In urban planning and map-making, we ourselves saw a glimpse of possibility

in the generative psycho-geographic practice a couple of weeks ago. The

map of surveillance cameras in New York City, generated by numerous individuals’

spontaneous participations and reports, shows the degree of comprehensiveness

that is unthinkable by a single researcher’s mind.[7]

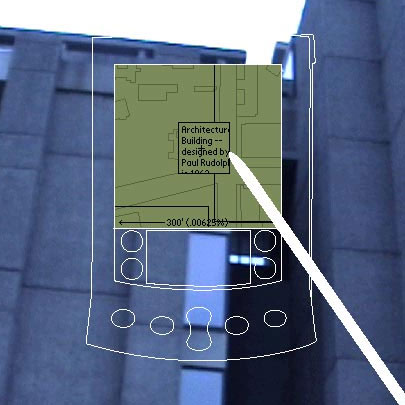

A similar example is the New York-based designer Rebecca Ross’s proposal

for a PDA-based tour of Yale University. [Fig.

1] Tourists of the University would be given Palm Pilots, by which

they could contribute their own experiences with particular locations:

‘Over time, the accumulations of these experiences becomes a community-authored,

or decentralised, map’.[8]

None of these would be relevant if not for the fact that we’re dealing

with the issues of identity and the city, and indeed, the identity of

a city. Without relying on the concept of ‘self-organisation’

or ‘emergence’, our very instincts would tell that the identity

of a city cannot be created overnight by certain individuals and imposed

upon from above. To us, it seems only decent to assume that the culture

of a city – distinctive or not – is something accumulated over

time, out of numerous unconscious activities and events – including

the banal and non-cultural ones. In this respect, the above examples seem

to suggest a new model for identity design, especially when it’s

dealing with such complex entity as a city. Instead of creating and imposing

certain visual attributes, can we design a system that would allow a city

to speak for itself? Instead of pondering on some ‘true’ representations

of a city, can we let the city directly present itself? Can we conceive

an ‘self-organising network’ for identity program, itself resembling

the city’s behaviour, and let the image of the city unpredictably

emerge out of the multiple inhabitants’ unplanned and unorganised

activities?

Multiplicity

For over decades, identity design has been one of the most lucrative and

influential business areas in graphic design. Its ability to create a

consistent ‘corporate image’ over a wide range of activities

and products has been a shining testimony to the profession’s competency.

In order to achieve such consistency, identity design has tended to pursue

the fixed, the static, and the homogeneous. All the products from one

manufacturer should somehow look the same with each other; the employees

of the company should share a common spirit manifested by their uniforms

and their standard letterheads; not only here, but also to the end of

the world; from now to eternity.

In reality, this dream has never been fulfiled: every now and then local

situations would force modifications and negotiations of global rules;

and it has never been free from plagiarism. One can say that the mixture

of the homogeneous and the heterogeneous, the fixed and the flexible,

has always existed in the project of identity design. Recently, however,

we have seen more conscious efforts to increase the open and flexible

elements in the mixture. Maybe it’s partly because the notion of

fixation itself has become unpopular and undesirable. But the practical

impossibility of predicting all the local situations has also become increasingly

clear, especially in the case of complex organisations. And since we’re

now dealing with one of the most complex organisations, it would be worthwhile

to be reminded of some examples of identity program that attempt to embody

the aspects of change and openness.

Bruce Mau Design’s identity for the Netherlands Institute of Architecture

(1993) consists of ‘100 logos, 1000 colours’ to reflect the

organisation’s multi-faced activities.[9]

[Fig. 2] Instead of a

single sharp-edged logo, they created multiple projection images that

would serve as a reservoir for different choices, allowing much flexibility.

Additionally, this set of almost amorphous logo-images would promote the

sense of movement and change, while still maintaining a substantial degree

of consistency. This mixture of consistency and freedom must have been

quite fresh a decade ago, and the fact that it’s still being used

may suggest its enduring conceptual strength.

The identity program of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (1995) takes

more definitely typographic approach.[10]

[Fig. 3] The most important

element of this program is a digital font developed by Mathew Carter.

The font contains, in addition to the standard Roman characters, various

elements that can be ‘snapped on’ to the characters to form

serifs or horizontal rules. Essentially, it was to give the in-house designers

a ‘toolkit’ to work with, rather than a finished product. The

Walker typeface would allow a sufficient room for variation, which was

desirable given the diverse nature of the organisation’s activities.

To our view, however, this project is more interesting in terms of the

new possibility for typography, than as a radical rethinking of identity

design. Too much of the characteristic is already determined by the core

letterform, rendering any other variations marginal.

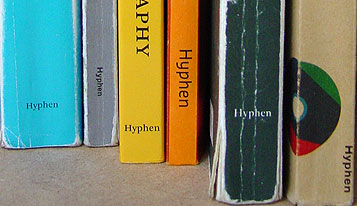

We can find a more extreme case in the London-based publishing house Hyphen

Press’s identity: or, the lack of it. [Fig.

4] Perhaps partly out of resistance to the prevalence of corporate

identity in design culture, it has never devised a fixed logo as a focal

point of ‘house style’.[11]

Instead, certain consistency over products is achieved more subtly by

the editorial policy, the books’ material quality and typographic

style – and most of all, a common ‘attitude’ towards design

and culture shared by its authors and the publisher. It should be quickly

noted that Hyphen Press is a fairly small adventure, with a limited range

of products, which would allow them a better control while avoiding militant

practice of corporate identity.

To the contrary, we can safely say that the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology (MIT) is indeed a huge and complex organisation. As a hothouse

of the open source movement (they are putting their course materials open

to the public), the MIT would appear only contradictory in keeping a fixed,

static identity. Although its current identity doesn’t show much

difference to those of other similar institutions, they have been maintaining

an interesting design policy for their web

site.[12] Anyone

– whether in the MIT community or not – can contribute one’s

own design for the main graphic element of the front page, which changes

every day. According to their design philosophy statement, the changing

appearance of the web site ‘reflects the diversity of MIT itself.

It does not represent a single voice, but rather many voices, showing

the Institute in a full and evolving way’.[13]

To our view, this idea seems more interesting than the ubiquitous ‘customising’

functions, because it’s about sharing your own creation with the

community, not about appropriating the generic for your own interest only.

Whether the design is beautiful or not is beside the point, but one may

wonder if it can be even more flexible, not only at the surface but also

on the structural level. Maybe in the near future…

Data-driven design

Attempts to introduce flexibility and fluidity in identity design, including

some of the earlier examples, have tended to display randomness and arbitrariness.

They may increase functionality of the program, and promote the sense

of multiplicity, but do not encourage more meaningful ‘reading’

of the dynamic form, because their visual properties are not related to

the changes in the world. The opposite effort to seek motivations in the

real-world events has been pursued in what is often called ‘data-driven

design’. Loosely associated with the field of information design,

it aims to visualise the invisible flow of data, and/or to embrace data

as a determinant factor in formal decisions. Sometimes, it doesn’t

stop at articulating information in a neutral way, but goes on to explore

the nature and the implications of what it expresses.

Curen_t_cy, created by Sung Joong Kim in 2002, is a machine that

issues the ‘smart money’.[14]

[Fig. 5] Specially designed

software tracks currency exchange rate information from the Internet,

and inscribes it in the form of encoded marks on the money. The issued

money would display its exact relative value at the time of printing.

Just like a snapshot, it would bear the hallmark of the moment.

Sulki Choi’s Daily World View (2003) map project is an example

of data-driven design that comments on the nature of the information it

deals with.[15] [Fig.

6] This map transforms itself in such a way to reflect our media-conditioned

interests in certain geographic areas. A search engine scans a designated

Internet news page, and counts the names of cities or countries appearing

on the page. The respective frequencies of the names affect the coordinates

of their locations. As a result, more frequently reported areas, that

is, more heavily interested areas, would occupy more space on the map,

dwarfing other ‘neglected’ regions. On the world map based on

New York Times, for example, the Middle East will appear prominently,

while Greenland will be on the verge of extinction.

Dan Michaelson and Tamara Maletic’s In the House project ‘taps

on’ the information traffic in the Gnutella community, a peer-to-peer

music-and-file sharing network.[16]

[Fig. 7] Three-dimensionally

erected, it captures search-words in the network and broadcasts them in

real-time, in a public space. It reports on the changing ‘ecology’

of a certain subcultural sector, by visualising the otherwise invisible

ebb and flow of searching activities. If it’s depressing to reconfirm

that one of the most heavily sought items is ‘hardcore’, then

it would be pleasantly surprising to find out that Fleetwood Mac is still

alive and kicking – at least on the Net.

Network-based, data-driven design, as exemplified by these works, may

suggest a new direction for identity design. Conventionally, identity

design has been in the realm of fancy and desire, in that it creates idealised

images, often removed from the reality of the body it represents. If we

could take a data-driven approach to the identity of a city, then we might

be able to relinquish control over image, and instead allow the city to

speak for itself, capturing both the liveliness of a living animal and

the truthfulness of its footprints. One final example demonstrates some

possibility in this respect. Twin

is an interactive typeface created by the Hague-based design studio Letterror,

for the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul in Minnesota, US.[17]

Connected to the on-line weather-report, it automatically changes

its form within certain parameters to reflect the change of whether in

the region. When the Twin Cities temperature reaches sub-zero degree,

the characters become formal and severe with its serifs. When it’s

warm, they become more relaxed and informal. Although the typeface is

only associated with the purely natural phenomenon, the commissioning

body found it culturally suggestive as well. Thus Janet Abrams, director

of the Minnesota University Design Institute, states that the typeface

is an ‘acknowledgement that [the Twin Cities are] always in flux’.[18]

If we push this possibility a little further, then we could imagine a

network-based software agent that collects relevant data directly from

the streets, and then visualises it to form a collective cultural image

of the city. In that case, the city itself would become a database, with

a means to express itself. Once given a voice, the city might be able

to speak much more eloquently than any single genius designer could do:

because, as a higher-level structure, a city is much smarter and more

complex than the sum of its dwellers’ intelligence.

What is to be done?

It should be clear now what we can make of all these ideas and insights.

We have argued for emergence and self-organisation as a model for the

identity of a city; the value of its multiplicity and fluidity; and the

possibility of incorporating data-driven design approach into identity

design. In brief, we are envisioning a network-based, data-driven, emergent

and dynamic identity of the city of Leuven.

What specifically can be done in this conceptual framework is still an

open question. We have been using the term ‘identity design’

in its conventional sense, with all those familiar elements and applications

such as the logo, typeface, letterhead, street sign, etc. Would it be

a foolish idea to take these age-old objects as a platform for such a

new approach? Not necessarily. Newness of the new idea might be better

manifested, and its value better judged, on the familiar ground. The logo

of a library that reflects the number of books checked out, a typeface

for a city that indicates different street noises in real-time, or a street

sign that somehow expresses the amount of beer being consumed: all these

can seem gimmicky, lacking the necessary depth and breadth to contribute

to the ‘collective image’ of a city. At least, however, they

might start pointing out a future direction for the identity of Leuven,

triggering a ‘self-organising’ process that will ultimately

lead us to the city as a database in its full sense.

But still, should we imagine something beyond those conventional boundaries

of identity design? Perhaps so. In effect, we have just outlined a new,

more specific design brief for the cultural identity of Leuven: many things

can be conceived in the framework, including those that are unimaginable

now and here.

Illusstrations

[Fig. 1] Rebecca Ross, A Tour of Yale

University

[Fig. 2] Bruce Mau Design, identity program

for Netherlands Institute of Architecture

[Fig. 3] Mathew Carter, typeface for the

Walker Art Center

[Fig. 4] Publications from Hyphen Press

[Fig. 5] Sung Joong Kim, Curren_t_cy

[Fig. 6] Sulki Choi, Daily World View

[Fig. 7] Dan Michaelson and Tamara Maletic,

In the House

Notes

[1] For an accessible

introduction to this process, see Steven Johnson, Emergence: the Connected

Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software, New York: Touchstone,

2001.

[2] Encyclopædia

Britannica. Retrieved December 14, 2003, from Encyclopædia Britannica

Premium Service <www.britannica.com/eb/article?eu=33091>.

[3] This game seems to

have multiple origins, but Conway’s one is the best known example.

It was first published in Martin Gardner, ‘Mathematical Games: the

Fantastic Combinations of John Conway’s New Solitaire Game “Life”’,

Scientific American, no.223, October 1970, New York.

[4] See, for example,

Manuel De Landa, A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History, New York:

Zone Books, 1997; and the same author’s Intensive Science and

Virtual Philosophy, New York: Continuum, 2002.

[5] See David Graeber,

‘The New Anarchists’, New Left Review, no.13, January/February

2002.

[6] The open source movement

was first founded in 1998 by a number of people who wanted to ‘persuade’

the protective industry by proving the collaborative production’s

superiority. The open source movement gained its crucial momentum in the

popularity of Linux operating system. See for more information: <www.opensource.org>.

[7] For further information

on this project, see: <www.mediaeater.com/cameras/info.html>.

[8] From Rebecca Ross’s

personal

web site.

[9] Project description

in the web

site of Bruce Mau Design; see, also, Will Novosedlik, ‘The Producer

as Author’, Eye, no.15, 1994.

[10] See, for more detailed

report, Moira Cullen, ‘The Space between the Letters’, Eye,

no.19, 1995, pp.70–7.

[11] It would be interesting,

in this view, to see how the publisher of Hyphen Press, Robin Kinross,

perceives the culture of design publishing. See Linda Eerme and Robin

Kinross, ‘The Architects of the Book’, originally published

in Domus, no.847, April 2002, and then posted on the Hyphen Press

web

site.

[12] The same example

is discussed in an essay proposing a new model for graphic design practice

based on the ideas of the open source movement. See David Reinfurt, ‘One

Possible Scenario for a Collective Future’, Dot Dot Dot, no.5,

2002.

[13] Web site philosophy

statement by Suzana Lisanti and the MIT home page team, published in their

web

site.

[14] For more information

on this project, contact its designer/programmer Sung

Joong Kim.

[15] For more information

on this project and its demonstration movie, see the web

site.

[16] In the House

is part of the United Air Project, initiated by Michaelson and Meletic

as an effort to develop multi-dimensional data-driven design approach

in urban contexts. For more information, see the project proposal posted

here.

[17] In addition to

this typeface project, the University of Minnesota Design Institute has

initiated many design projects that are relevant to current discussion

on city identity.

[18] Quoted in Matthew

Mirapaul, ‘Is It About to Rain? Check the Typeface’, New

York Times, July 24, 2003.